Still-life paintings from the Dutch Golden Age are known for their austere yet exquisite beauty. Plump fruits, exotic delicacies and scrumptious breakfast foods are painted with such delicious realism that it makes you want to lick the canvas. (As a museum curator I implore you to restrain yourself.)

But nothing in these paintings were chosen at random. 17th century Dutch artists carefully selected every object for their symbolic meanings, usually to express Christian themes and morals.

One fruit in particular hides a fascinating, sexy meaning: the medlar. Read on to discover how artists of the 1600s used these unusual fruits as the prostitutes of the fruit bowl.

Rotten before they’re ripe

Medlars have been cultivated since Ancient times, but reached their height of popularity in the 1600s. The strange-looking fruit tastes like stewed apples and quince, and their thick peel has a deep russet or rich bronze colour. In the UK, the poor medlar is sometimes known as “dogs’ arse fruit” or “open-arse fruit” because of the rather unattractive open calyx on one side.

But the really unusual thing about this fruit is that medlars are not edible until they’ve already begun to rot. (A process that modern science calls bletting.)

Dutch Golden Age artists loved the symbolic potential of a fruit that is rotten before it’s ripe. And they weren’t the only ones, either: in literature, medlar symbolism is used by writers like Chaucer, Shakespeare, and D.H. Lawrence, among others.

Medlars as prostitution symbols

For Dutch artists, a fruit rotten before it is ripe was the perfect way to represent the ruination of purity. So whenever you see medlar fruits in a painting of this era, it is intended to symbolize prostitution, wantonness, and decaying morals.

That’s right: although these still -life paintings look pretty and conservative at first glance, the artist secretly wants you to be thinking about prostitutes.

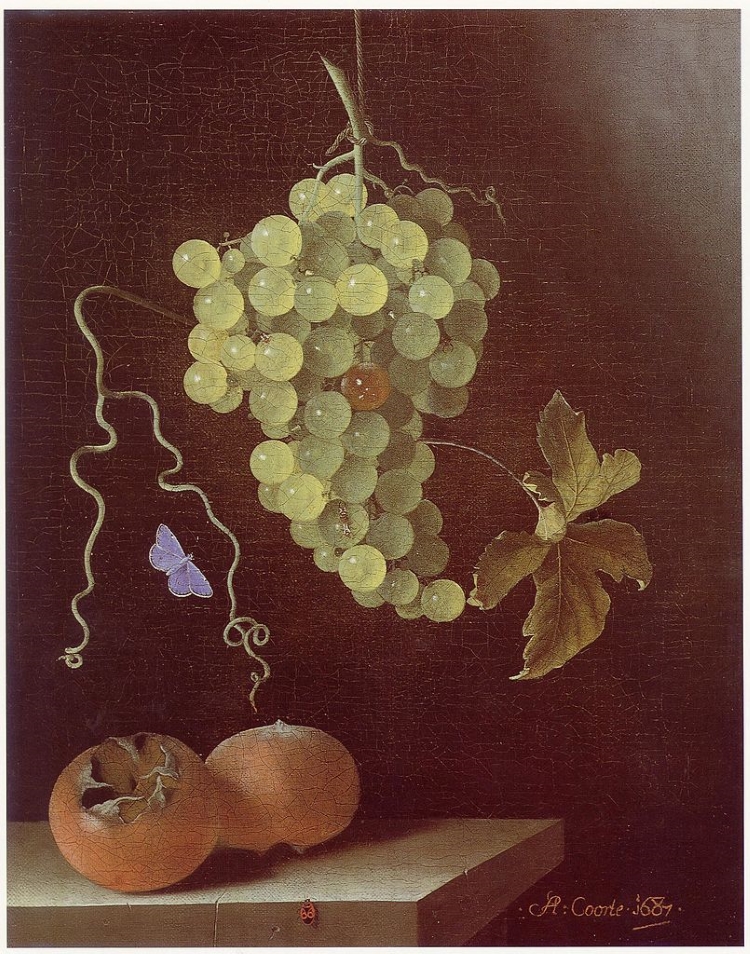

Take, for example, the painting above by Adriaen Coorte. In it, two medlar fruits sit below a cluster of grapes and a purple butterfly. Here, grapes can be understood to symbolize Christ, a nod to the wine given by Jesus to his disciples at the Last Supper. The butterfly — having transformed from a caterpillar — symbolizes the transformation or salvation of the soul.

Taken all together, Coorte’s still-life contains an important moral message: the juicy medlars, which represent prostitutes and other impure souls, are offered a path of redemption through Christ.

Brothel paintings

Medlar fruit in still-life paintings relate to another popular genre in Dutch Golden Age art: paintings of brothel scenes (bordeltjes).

These paintings usually depict beautiful young prostitutes presided over by a hideous older madame. Together, these saucy women supposedly lure respectable young gentlemen from good families into sin and vice.

Brothel paintings were most often found in the homes of respectable and well-to-do families during the Dutch Golden Age. Although clearly painted to amuse and titillate, their primary intention was its moral message.

For young men, brothel paintings were intended as a stern warning not to become the foolish and hapless victims of wily women. (Ha!) For young women, the consequences of female sin and lust are cruelly etched into the face of the ugly older madame.

This also relates to the tradition of vanitas paintings, in which skulls, rotting fruit and wilting flowers serve to remind the viewer of the transience of life. Likewise, brothel paintings are a stark reminder of the passing nature of one’s youth and beauty.

From brothel to fruitbowl

Like the brothel scenes, medlar paintings have a similar moralizing purpose. Although these still-lives might have catered to more modest tastes, medlar symbolism intended to impart the same warning against prostitution and other vices.

The Dutch Golden Age was a prosperous time, and its unusually large pool of art collectors favored paintings that reflected their moral and spiritual beliefs. However, the Dutch Calvinists — a branch of Protestantism that formed the dominant religious group of the day — frowned upon much blatant religious imagery. As a result, artists of this era tended to cloak moralistic and religious messages in other forms of genre painting.

In the painting below by Jacob Marrel, for instance, a snail wisely chooses to go toward the righteous Christian grapes and away from the temptation of the luscious medlars.

What to do with your lust?

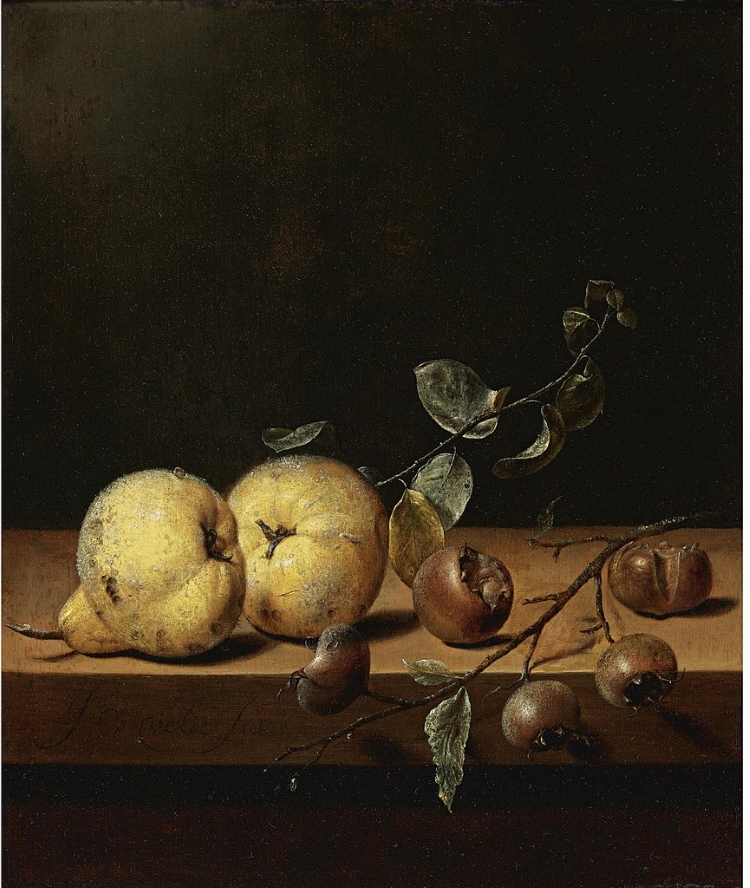

The theme of making good Christian choices is also subtly present in the painting by Martinus Nellius, below. Here, medlars sit alongside juicy quince fruits — an Ancient emblem of marriage and fertility.

According to Pliny, a cutting from the quince tree would form another tree when planted. The quince was therefore associated with spiritual immortality, as well as female fertility.

Thus, the artist is offering two outcomes for all your filthy female lust. You can go the way of the quince, and achieve eternal grace through marriage and reproduction. Or you can go the way of the medlar, towards prostitution and spiritual ruin.

Just to make sure the message isn’t too subtle, the artist chose to lay the fruit on a table held up by this spicy carving of a bare-breasted woman. So choose your fruit wisely!

I’d like to acknowledge author & cartoonist Iron Spike and blogger Messy Nessy Chic for first introducing me to the symbolism of medlars. Show them some love by following their great work! If you’re hungry for some further reading about the symbolism in Dutch Golden Age painting, here are some other sources that I found interesting: Mearto; The Met; Artsy.

If you’ve gone this far into an article about prostitution symbols in Dutch painting, I think you’d also enjoy this one on sexy weasels in Renaissance art.

And don’t forget to subscribe to The Museum of Ridiculously Interesting Things below, or follow me on Instagram or Facebook to make your life a little bit weirder!

Pingback: Merkwaardig (week 22) | www.weyerman.nl